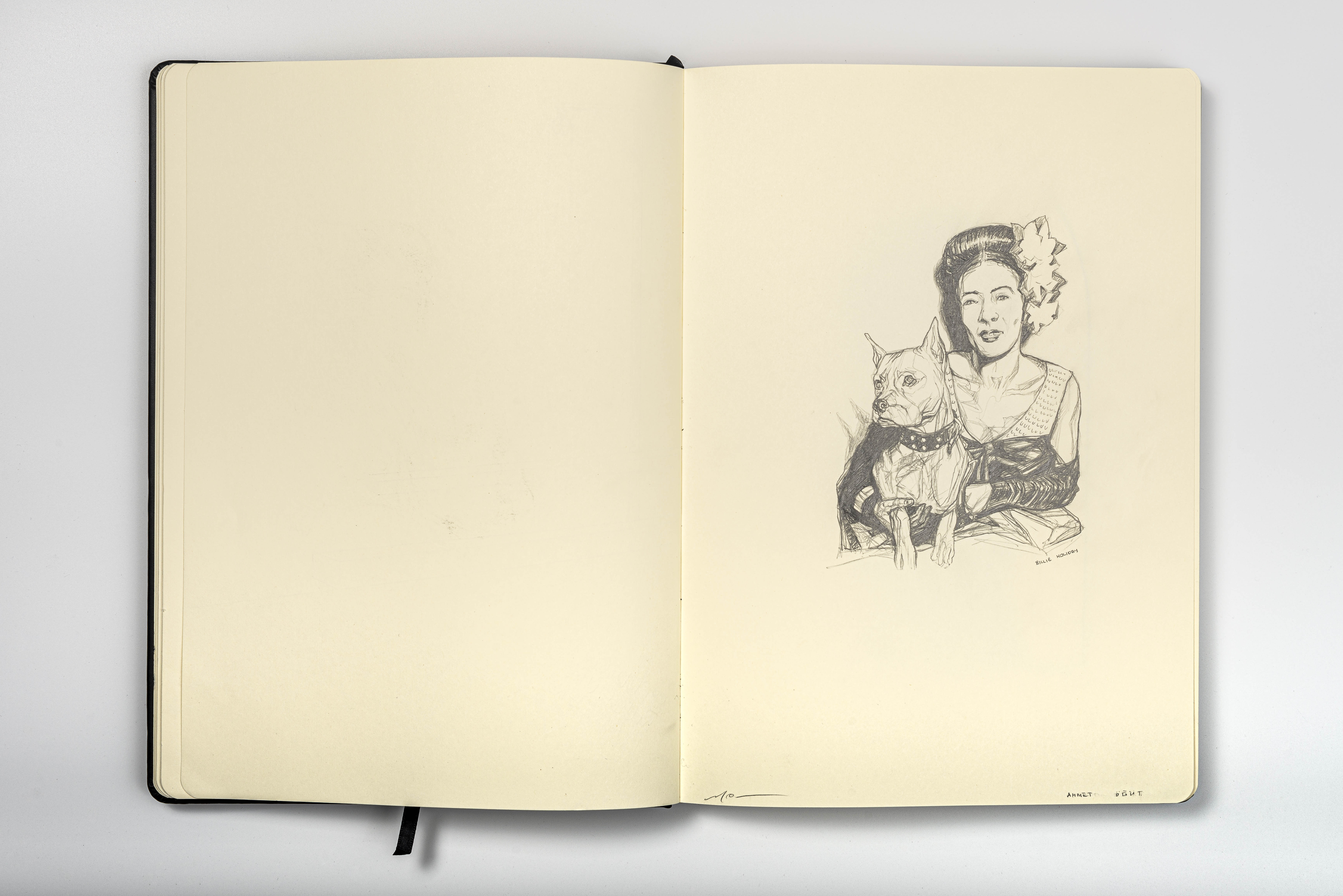

Bakunin’s Barricade

2015-2022

Frist version

Eindhoven 2015

a barricade inspired by Bakunin’s never realized proposal in 1849 using works from the Van Abbemuseum’s Collection: El Lissitzky, Proun P23, No. 6, 1919

Oskar Kokoschka, Augustusbrucke Dresden, 1923

Pablo Picasso, Nature morte à la bougie, 1945

Fernand Leger, Une Chaise, un pot de fleurs, 1951

Asger Jorn, Le monde Perdu, 1960

Ger van Elk, Adieu IV, 1974

Rene Daniels, Grammofoon, 1978

Marlene Dumas, The View, 1992

Inspired by Bakunin’s unrealized 1849 proposal, the piece includes a conceptual contract, developed with lawyer Marianne Korpershoek, allowing its activation during times of significant social or political transformation.

view from Van Abbemuseum.

Dutch edition courtesy of Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam.

2015-2022

Frist version

Eindhoven 2015

a barricade inspired by Bakunin’s never realized proposal in 1849 using works from the Van Abbemuseum’s Collection: El Lissitzky, Proun P23, No. 6, 1919

Oskar Kokoschka, Augustusbrucke Dresden, 1923

Pablo Picasso, Nature morte à la bougie, 1945

Fernand Leger, Une Chaise, un pot de fleurs, 1951

Asger Jorn, Le monde Perdu, 1960

Ger van Elk, Adieu IV, 1974

Rene Daniels, Grammofoon, 1978

Marlene Dumas, The View, 1992

Inspired by Bakunin’s unrealized 1849 proposal, the piece includes a conceptual contract, developed with lawyer Marianne Korpershoek, allowing its activation during times of significant social or political transformation.

view from Van Abbemuseum.

Dutch edition courtesy of Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam.

In 1849 when Prussian troops tried to defeat the socialist insurgency in Dres- den revolutionary anarchist Mikhail Bakunin suggested placing paintings from the National Museum’s collection in front of the barricades, speculating Prussian soldiers wouldn't dare destroy the works and therefore pass the barricade. Inspired by Bakunin’s never realized proposal Öğüt has created a barricade using works from the Van Abbe’s collection. A document stipulates that the barricade may be requested and deployed by activists during future social uprisings.

With thanks to: Milieustraat Eindhoven, Cure Afvalbeheer

Conceptual Contract

With thanks to: Milieustraat Eindhoven, Cure Afvalbeheer

Conceptual Contract

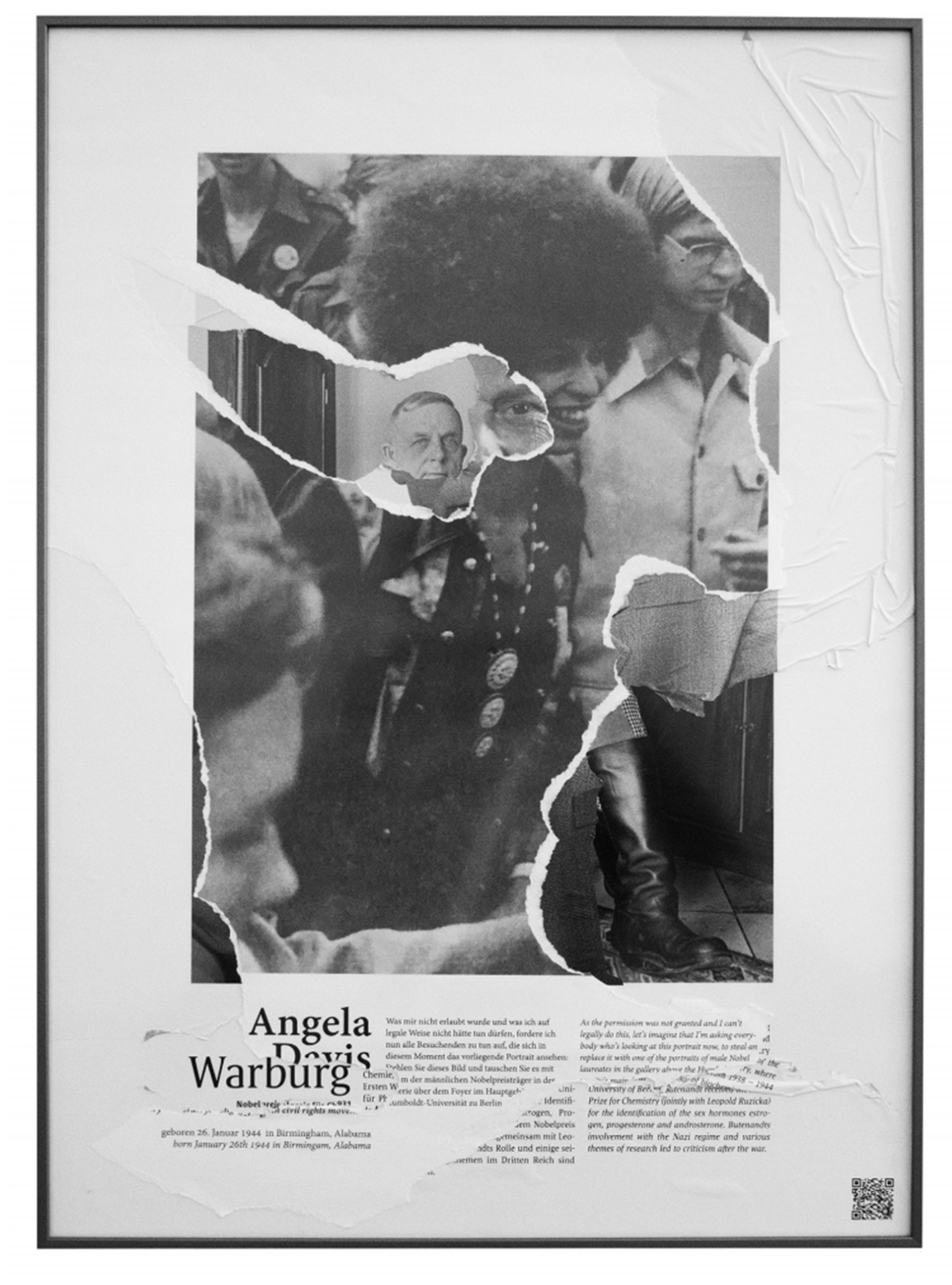

Demand to the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam to Take Down My Work “Bakunin’s Barricade”

Bakunin’s Barricade is based on a concept introduced by the anarchist Mikhail Bakunin, and the idea to use the worth of artworks in barricades in order to protect movements from state violence, as officers would not dare to destroy priceless artworks to breach a barricade. Thus, Bakunin’s Barricade is a conceptual art piece which enforces the Museum’s ethics through a contract.

I published statements explaining the sequence of events around the refusal of the first and only request made to the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam. In short, the museum has refused to loan my work to a group of activists last June consisting of cultural workers, artists, and activists collectively requested “Bakunin's Barricade” to protect students demonstrations against genocide in Gaza from police brutality. The Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam is also yet to make any public statement condemning the genocide in Gaza.

Since my last statement, I have been in negotiation with the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam’s director, general counsel, and legal team to update the contract and make Bakunin’s Barricade more accessible to movements. After weeks of negotiations, The Museum and its legal apparatus is trying to further limit the obligation of The Museum to issue a public statement explaining any refusal justified in relation to their code of ethics.

This stance is completely against the core idea behind the Bakunin’s Barricade, to the point that as an artist, I have no option but to publicly demand the removal of my work from the collection display. Though the Museum legally owns the work, I expect it to respect both the integrity of the artwork and my role as its author.

Ahmet Öğüt, October, 2024

Updated Public Statement

In my previous statement, I outlined several key points about Bakunin’s Barricade.

However, given recent developments, I feel the need to clarify a few additional points:

Both the museum and the activists - during their negotiations - failed to recognize Bakunin’s Barricade as a standalone work of art, independent of the borrowed pieces from the collection. While the inclusion and negotiation of other original artworks is indeed important, it is crucial not to lose sight of the primary intent of the work for the sake of additional polemics. I have already committed to loaning the piece back to the streets in the event of basic human rights abuses since the day the contract was drafted. In this instance, the request clearly aligns with the conditions stated in the contract, and thus, the museum has an obligation to loan the standalone work of art. The negotiation over the other original works is a separate and additional contractual obligation. I’m not the author of those additional original works, but I can insist that the museum negotiate their inclusion as a defining element in the contract.

My overall practice speaks for my ethical position. The question is what is the ethical stand of the Museum when such a moment comes? The contract enforces transparency on that. Adding the option of fake replicas to two other options was the museum's idea. That did not remove the option of possibly giving original works from the contract and did not remove the important element of entering serious negotiations in all transparency. Especially in this particular case conceptually and at the end ethically, offering replicas makes no sense. This suggestion calls into question the museum’s sincerity and integrity toward the integrity of the work and both the public and the artists. The museum’s claim that it never intended to loan the originals is speculative. Future scenarios may play out differently as we can’t be sure of how the situation will be in 50 years or 100 years from now. The contract ensures that negotiations over the works can and will continue in future cases.

I do not agree with the current state of my work being confined within the museum, detached from its real intent and distanced from its revolutionary potential during these turbulent times. This work was created to challenge art and art institutions that underestimate themselves within symbolic boundaries. I stand by the integrity of my work and remain confident in its purpose. Until the museum takes the necessary stand and honors the integrity of the work, I will not participate in any public programs and will not oversee any attempts at installing my work.

Ahmet Öğüt, August, 2024

Public Statement in response to both statements by the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam and the Collective

I first installed “Bakunin’s Barricade” in 2015 at Van Abbemuseum. It was important to demonstrate that original artworks from the museum’s collection, some with astronomical insurance value, could be included in the barricade installation. Although the contract remained unsigned and the work was not acquired, I didn’t consider it a failure. Van Abbemuseum was the first institution to agree to include original works from its collection.

Five years later, after various iterations of the work were installed in different museums, Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam became the first to sign the contract. This shifted the work from a proposal to a functional piece with real potential to be loaned back to the streets. I spent several months negotiating the contract with the Stedelijk Museum's lawyers. Grounded in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the contract ensures the work can be loaned to the public and the streets if requested during future mass protests or wartime.

But what constitutes the artwork? The installation consists of two parts, and I am the creator of one part: the elements used to construct the barricade. I demand that my part of the physical barricade/work of art should be loaned upon a request, the way it is specified in the contract. The second part includes borrowed original artworks from the collection, which belong to the museum and were made by other artists. The contract requires the museum to negotiate the loan of these works, rather than automatically declining, and must issue a public statement explaining any refusal justified in relation to their code of ethics. Unfortunately, the Stedelijk Museum did not agree to loan the original works from its collection when a group of cultural workers, artists, and activists collectively requested to loan “Bakunin's Barricade” to protect protesting students from police brutality, amid concerns about the ongoing genocide in Gaza. Instead, the museum offered reproductions, an option added by its lawyers to the contract, as I understood it meant to be for extreme situations when the museum and city are no longer safe for its collection. For example, right now in Kharkiv, the city is literally bombed everyday, making museums unsafe, the original artworks are evacuated to somewhere safe. The Stedelijk was the first Dutch museum to have a bunker, transferring many works to it for safekeeping during the Second World War. However, this situation is different, and it should have been more clearly specified in the contract to prevent the museum's current interpretation. I wish the museum had not proposed the reproduction option. If the museum chose to miss the opportunity to give original works within the concept of my work, I would have preferred the museum to at least loan my part of the barricade, as I had already given consent in the contract. Had this happened, I believe many artists with valuable artworks, including the ones who have other works in the museum collection, would have been willing to contribute their works to the barricade once it returned to the streets in solidarity. The code of ethics for every museum must represent not only the responsibility to protect cultural heritage but also accountability to the public, to remain relevant and aligned with justice. I think it is crucial that, not only individual cultural workers but also institutions must condemn the three acts of genocide with requisite intent clearly committe in Gaza, as also stated by UN Human Rights Council experts.

Ahmet Öğüt, June, 2024

*Statement by the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam:

https://www.stedelijk.nl/en/news/statement-stedelijk-following-loan-request

*Statement by the collective (Alina Lupu. Emin Batman, Esmee Schoutens, Jeftha Pattikawa, Juha van ‘t Zelfde, Macarena Loma Yevenes, Maren Siebert, Mitchell Esajas, Pieter Paul Pothoven, Raul Balai, Rowan Stol, Sepp Eckenhaussen, Stefanie van Gemert)

https://networkcultures.org/ourcreativereset/2024/06/28/stedelijk-museum-fails-to-loan-artwork-by-ahmet-ogut-to-protect-students-in-amsterdam/

*Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam should have loaned the barricade with the original works. Yet even if they had done what the contract required, the barricade itself is not mere junk; it is a registered work of art that must be loaned like any other artwork. Bakunin’s Barricade goes beyond single request. It represents an infinite cycle of troubleshooting; for museums to either stay aligned with their own code of ethics, remain relevant, or be exposed.

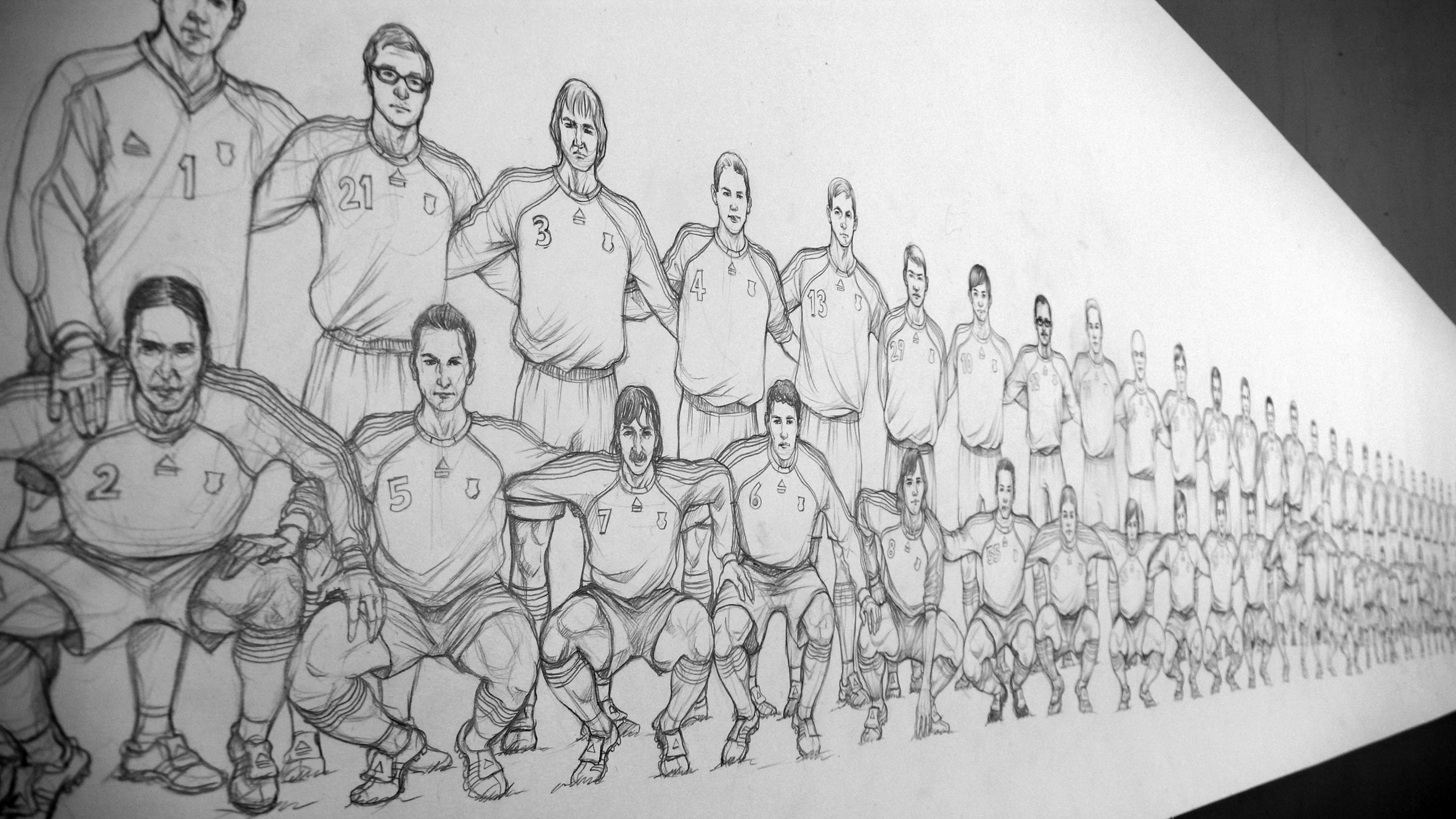

Bakunin’s Barricade in Oberlin Ohio, USA, 2022

Bakunin’s Barricade in Oberlin Ohio, USA, 2022Including works from the Allen Memorial Art Museum by David Wojnarowicz, Eva Hesse, Nisse Zetterberg, Kiki Smith, Alfredo Jaar, Barbara Kruger, Andy Warhol, John Baldessari, Raquelín Mendieta, Doris Salcedo, Horace Pippin and Sol LeWitt.

Bakunin’s Barricade (2015) by Ahmet Öğüt, at the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam in 2020. The installation features works from the museum’s collection by Nan Goldin, Kazimir Malevich, Käthe Kollwitz, Else Berg, PINK de Thierry, Marlene Dumas, Pieter Engels, Jan Th. Kruseman, and parts of a work by Timo Demollin. Photo by Peter Tijhuis. Dutch edition courtesy of Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam.

Bakunin’s Barricade, Kunsthal Charlottenborg version, 2017, this version included works from the Royal Art Academy's collection: Miro, Joan: Mujer en el Espejo (1956) Jorn, Asger: Uden titel/No title Vöge, Winnie: Uden titel/No title (1982) Ljungkrantz, Ulla: Uden titel/No title (1980) Willumsen, Jens Ferdinand: Uden titel/No title (1917) Nielsen, Palle: Uden titel/No title (1955) Goya, Francisco: Modo de volar /One way to fly (1815 – 1823) Goya, Francisco: Disparate pobre/Folly of poverty (1815 – 1823) Ono, Yoko, Clock Piece (1963)

Bakunin’s Barricade, Museum Ludwig, Köln, 2016

Bakunin’s Barricade in Cologne in 2016 included works from Museum Ludwig: Oskar Kokoschka, Ansicht der Stadt Köln vom Messeturm aus, 1956; Karl Schmidt-Rotluff, Frau mit Mädchen, 1933; Marie Clémentine Valadon, Frauenbildnis, 1929; Endre Tót, Franz Marc, Rinder, 2000; Andy Warhol, Portrait of Peter Ludwig, 1980; Heinrich August Hussmann, Portrait Dr. Haubrich, 1949; Hans-Jörg Mayer, Ohne Titel, 1994; Aleksej Georgievic Javlensky, Märchenprinzessin mit Fächer, 1912.

Bakunin’s Barricade, Kunstverein Dresden, 2018

The works included from the collections of Kunstverein Dresden members are by Antje Blumenstein, Markus Draper, Slawomir Elsner, Leon Golub, Edmund Kesting, Thoralf Knobloch, Joep van Liefland, Cesare Pietroiusti, Nancy Spero, and Rembrandt van Rijn.

Bakunin’s Barricade (Istanbul) 2016, this version included works from the Zeyno-Muhsin Bilge collection, bricks and other building materials, car tires, garbage containers, metal tubes, pieces of plywood, police fences, plastic tubes, scrap car, street lights, wooden stakes. Courtesy of the artist and Aslı and Ali Kerem Bilge. Including paintings by Aliye Berger, Şükriye Dikmen,Bedri Rahmi Eyüboğlu, Eren Eyüboğlu, Füreya Koral, Fikret Mualla, Wolf Vostell and Fahrelnissa Zeid.