Freedom Square

2025

ceremonial intervention.

commissioned by steirischer herbst.

photo: steirischer herbst / Daniel Kindler

2025

ceremonial intervention.

commissioned by steirischer herbst.

photo: steirischer herbst / Daniel Kindler

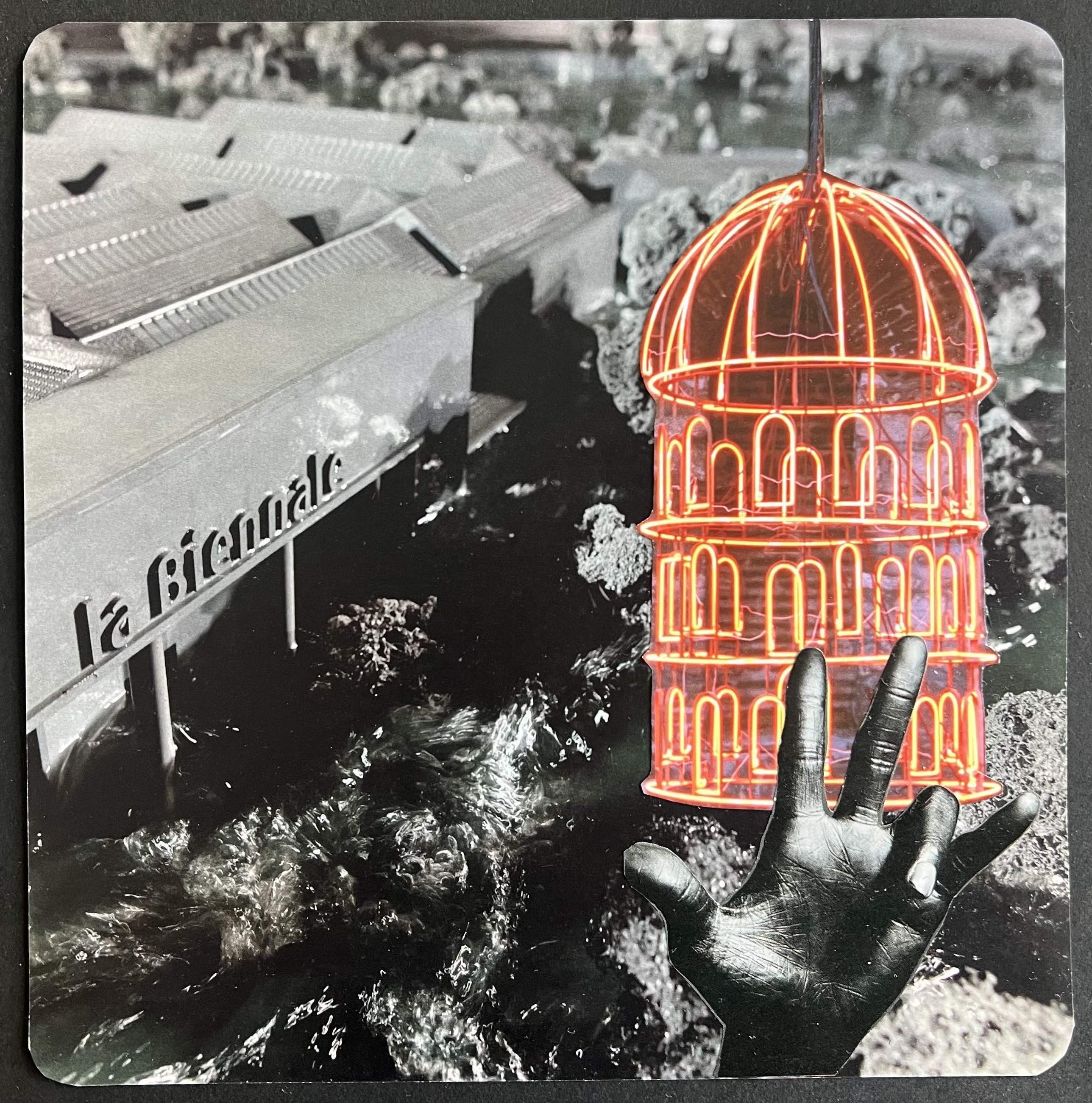

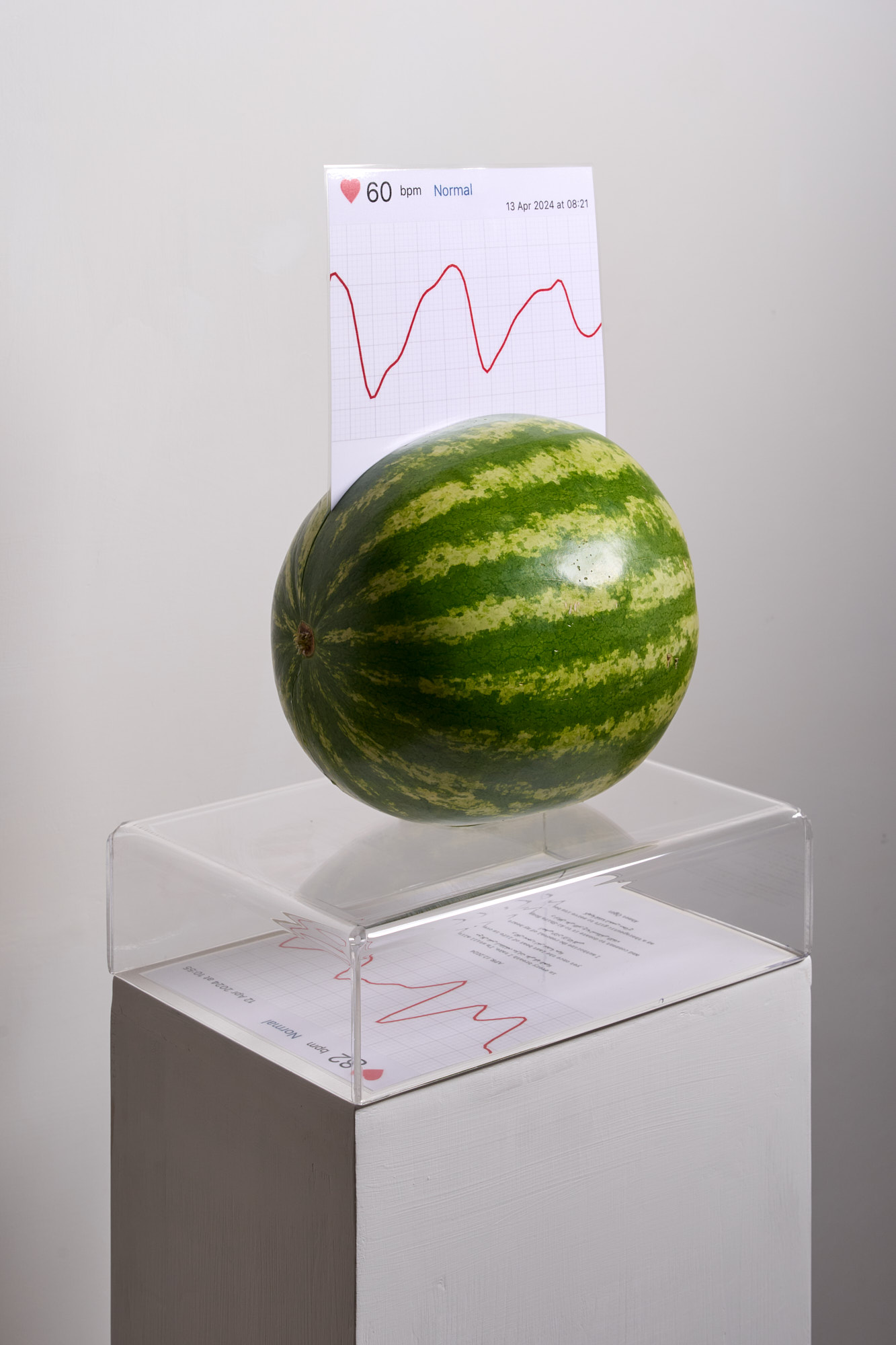

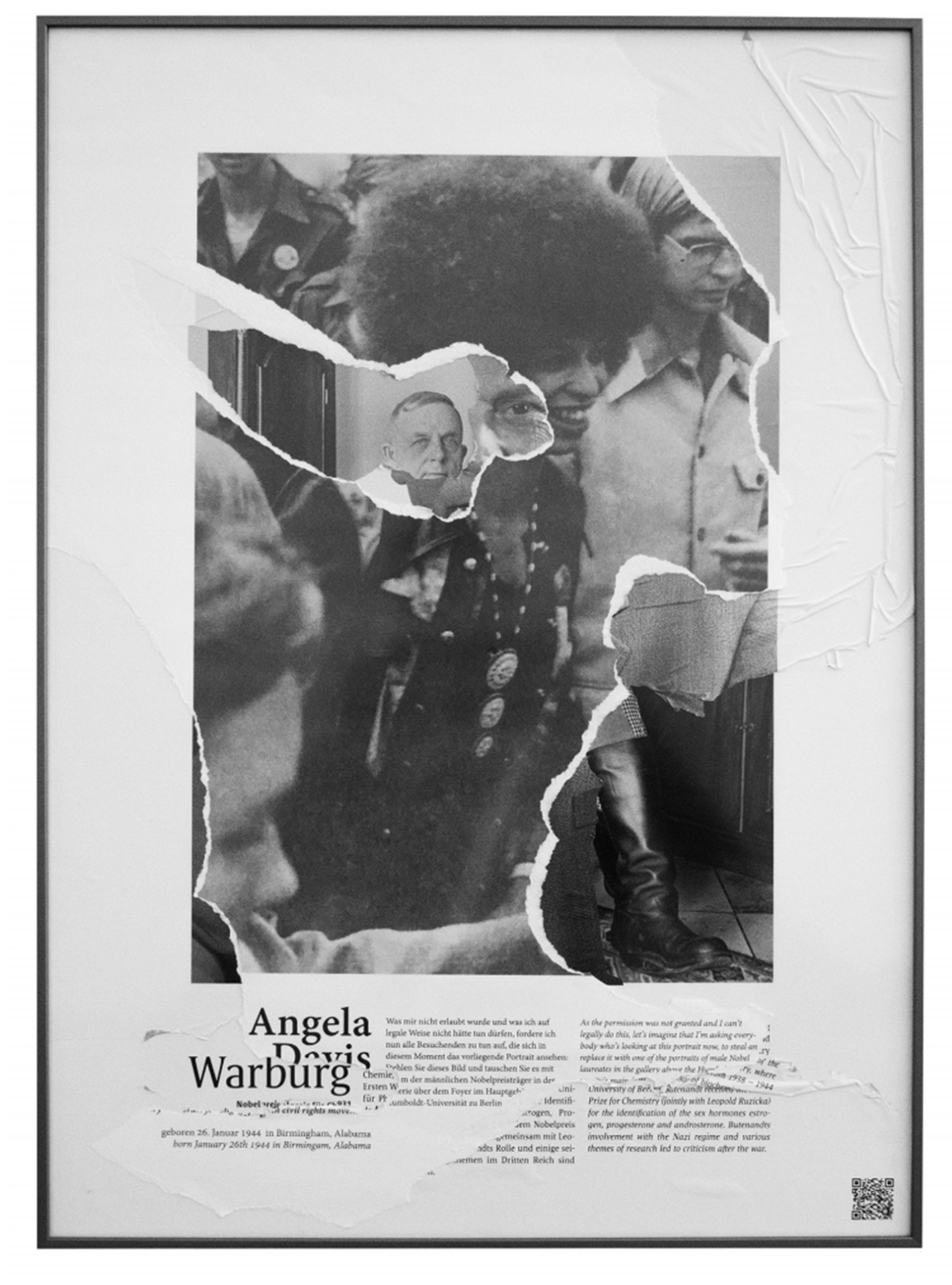

Renaming of Freedom Square to Freedom Square. Freedom Square is a ceremonial intervention. Formerly Franzensplatz, has been renamed Freedom Square in 1938 by the Nazi occupation. We no longer have to live with the 1938 version of freedom! Throughout history, right-wing extremists have often twisted words like freedom, which once stood for justice, equality, and liberation, for their own purposes. Currently in the world there are many Far-right, nationalist, and anti-immigration political parties hijacking the word freedom: Freedom Party of Austria (FPÖ), The Party for Freedom (PVV), in the Netherlands, Switzerland’s Freedom Party (FPS) In the Czech Republic, Freedom and Direct Democracy (SPD), Freedom and Solidarity (SaS) in Slovakia, Albania’s Freedom Party (PL), in the United States, the Freedom Caucus, a far-right congressional group within the Republican Party, Canada’s Ontario Freedom Party and in Australia, the Freedom Party of Victoria. Reclaiming freedom today is therefore not just a symbolic act; it is urgently necessary. Freedom must be redefined in solidarity with those who are still fighting for freedom. Lawyer Dr. Rahim Rastegar, witnessed the name change legally, as well as Artistic Director and Chief Curator steirischer herbst.

.

Welcome to the ceremonial renaming of Freedom Square to Freedom Square.

As we know, Freedom Square, formerly Franzensplatz, has been renamed Freedom Square twice: in 1918 and 1938. Are we still living with the freedom of 1938?

Throughout history, right-wing extremists have often twisted words like freedom, which once stood for justice, equality, and liberation, for their own purposes. Currently, there are many far-right nationalists in the world hijacking the word “freedom.” Here I would like to mention a few examples:

Across various countries, numerous political groups incorporate “freedom” in their names while promoting a range of right-leaning, nationalist, or populist ideologies. In Austria, the Freedom Party of Austria (FPÖ) is a far-right, nationalist, and anti-immigration party with a Euroskeptic stance. The Party for Freedom (PVV) in the Netherlands, founded by Geert Wilders, is similarly anti-immigration, anti-Islam, and Euroskeptic. Switzerland’s Freedom Party (FPS) was a nationalist, right-wing populist group. In the Czech Republic, Freedom and Direct Democracy (SPD) promotes nationalist, anti-immigration, and Euroskeptic views. Freedom and Solidarity (SaS) in Slovakia leans libertarian, combining economically right-wing policies with more centrist social positions. Albania’s Freedom Party (PL) follows a conservative, nationalist orientation. In the United States, the Freedom Caucus, a far-right congressional group within the Republican Party, exerts significant influence, though it is not a standalone party. Canada’s Freedom Party of Ontario claims to be founded on a blend of liberal and conservative principles. Meanwhile, in Australia, the Freedom Party of Victoria, a right-wing microparty, gained attention for endorsing the No vote during the 2023 Indigenous Voice referendum. Despite varied contexts, these groups often use the rhetoric of “freedom” to advance nationalist or conservative agendas.

Reclaiming freedom today is therefore not just a symbolic act; it is urgently necessary. Freedom must be redefined in solidarity with those who are still fighting for freedom.

We must ask ourselves:

What does freedom mean today, especially in Europe, where we see the rise of fascism, forced migration, and growing inequality?

Who is allowed to move freely?

Who is allowed to speak?

Who has the right to gather, to protest, to express an opinion—or simply to be visible in public?

What does it truly mean to reclaim freedom?

For us, freedom is not a narrative of nationalism, but something we share.

It is not about power over others, but about living together in peace.

It is not freedom for a few while others are excluded, but a freedom rooted in care, solidarity, and fairness for all.

In your presence, we register this as the first step toward liberating “freedom.”

Thank you for being witness to this act of redefinition.